On any given day America incarcerates tens of thousands of youth within the juvenile justice system

Anytime a youth is deprived of their liberty, that youth is incarcerated. Throughout the U.S., places that incarcerate youth come in many forms and take on various names; training schools, diagnostic centers, assessment centers, residential treatment facilities, wilderness camps, forestry camps, shelters, boot camps, detention centers, juvenile halls, juvenile correctional centers, youth study centers, campuses, cottages, youth development centers, academies, challenge centers, youth centers, children’s centers, youth camps, group homes, and girls or boys schools. These institutions are often named after the town or region where they are located, and on occasion after nearby geographic features such as mountains, lakes and rivers. These vague or pleasant names often obscure the fact that these facilities echo some of the most abusive elements of adult incarceration; solitary confinement, physical and sexual abuse, physical and chemical restraints, and widening margins of racial disparity. Click here for the latest youth incarceration data. For more background, read the “Locked Up: What is a youth prison?” series.

Disparate Geographies: How Race, Ethnicity, Gender, and Geography Impact the Incarceration of America’s Youth

Arrests of youth (youth ages 0–17) peaked in 1996 at nearly 2.7 million. The Department of Justice reports that arrests of youth have since declined—the number in 2016 was 68% less than the 1996 peak. In comparison, arrests of adults fell 20% during the same period. Yet there are too many youth are still locked up, and racial disparities among committed youth have widened. This data shows that youth of color are much more likely to be incarcerated despite the fact that they commit roughly the same level of juvenile crime as white youth. According to the Haywood Burns Institute, African-American youth are 5 times more likely to be incarcerated than white youth, Native American youth are 3.2 times more likely to be incarcerated than white youth, and Latino youth are 2 times more likely to be incarcerated than white youth, and in some individual states, this disparity is profoundly higher. Moreover, research from the National Council on Crime and Delinquency shows that disparities are increasing in some jurisdictions. Our brief on Virginia and New Jersey’s campaigns to abolish youth prisons through a racial justice lens highlights the strategies undertaken by the state campaigns to place racial inequality at the center of their efforts to end youth incarceration, and shows that centering youth justice as a racial justice issue is key to successful campaigns that convince decision-makers to put kids on a better path, instead of putting them behind bars.

According to the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, girls make up 15% of youth in residential placement. Girls are now making up a larger share of the juvenile justice population at every stage of the process. According to Gender Injustice: System-Level Juvenile Justice Reforms for Girls over the past two decades, girls share of the juvenile justice system from courts through incarceration saw sizeable increases: arrests increased 45%, court caseloads 40%, detentions jumped 40%, while post-adjudication placement rose by 42%. Gender inequities falling heaviest on girls of color and LBQ/GNCT (lesbian, bisexual, questioning / gender-non-conforming, transgender). Girls of color are much more likely to be incarcerated than white girls. The placement rate for all girls is 47 per 100,000 girls (those between ages 12 and 17). For white girls, the rate is 32 per 100,000. Native girls (134 per 100,000) are more than four times as likely as white girls to be incarcerated; African American girls (110 per 100,000) are three-and-a-half times as likely; and Latina girls (44 per 100,000) are 38% more likely. Though 85% of incarcerated youth are boys, girls make up a much higher proportion of those incarcerated for the lowest level offenses. Thirty-eight percent of youth incarcerated for status offenses (such as truancy and curfew violations) are girls. More than half of youth incarcerated for running away are girls.

LGBTQ youth represent 5- 7% of the nation’s overall youth population, but they compose 13-15% of those currently in the juvenile justice system. In secure detention or correctional facilities, LGBTQ youth are especially at risk as they face harassment, emotional abuse, physical and sexual assault, and prolonged periods spent in isolation. In addition, a 2016 report from the Movement Advancement Project (MAP), finds that one in five youth in the juvenile justice system identify as LGBTQ and 85% of these youth are youth of color. LGBTQ youth are vulnerable to discrimination, profiling, and mistreatment in the juvenile and criminal justice systems. In fact, LGBTQ youth are twice as likely to end up in juvenile detention while 20% youth in juvenile facilities identify as LGBTQ compared to 7-9% of youth in general.

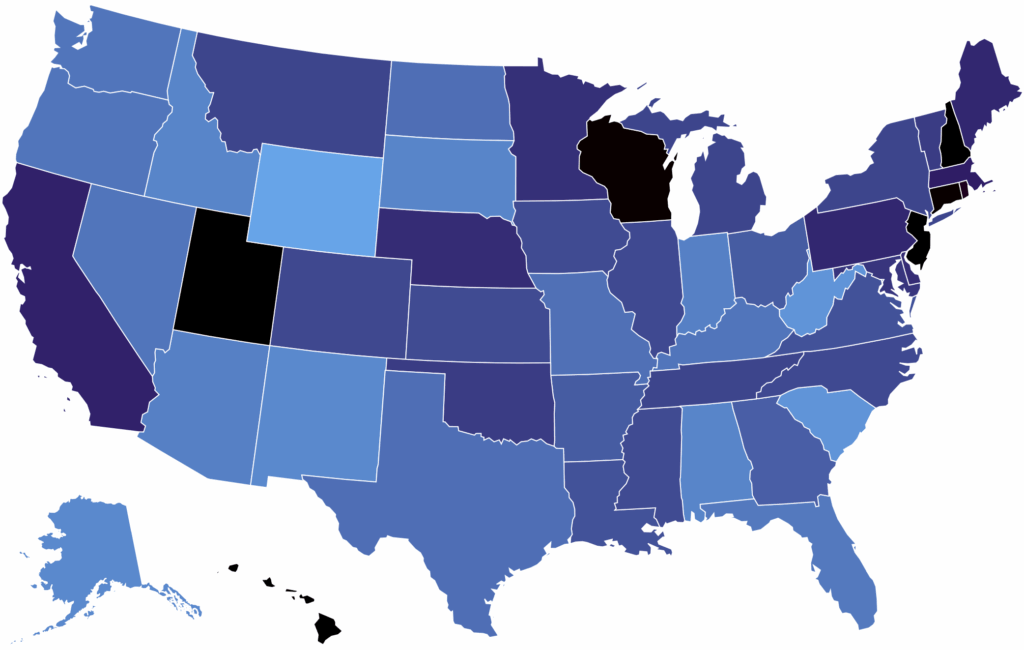

Charting trends of racial and gender injustice across the juvenile justice system

This map includes rates of incarceration for each state broken out by race, ethnicity, and gender. Custody rates are calculated per 100,000 juveniles ages 10 through the upper age of original juvenile court jurisdiction in each State.

Sources: The data on incarcerated youth and general youth population is sourced from the Census of Juveniles in Residential Placement 2015 from the U.S. Department of Justice’s Office of Juvenile Justice & Delinquency Prevention available online at: http://www.ojjdp.gov/ojstatbb/ezacjrp/

Desperate Topographies: Visualizing America’s Oldest and Largest Youth Prisons

One of the most harmful, ineffective and expensive forms of incarceration is the youth prison, the signature feature of nearly every state juvenile justice system. States devote the largest share of their juvenile justice resources to youth prisons at an estimated annual cost of over $5 billion per year. While youth incarceration has dramatically decreased over the past decade, almost all states still rely on these costly institutions and the harmful approach they embody. If youth prisons were closed, tens of millions of dollars could be freed up for community-based, non-residential alternatives to youth incarceration, and other youth-serving programs. In October 2016, the National Institutes of Justice, in partnership with the Annie E. Casey Foundation and the Harvard Kennedy School, published The Future of Youth Justice: A Community-Based Alternative to the Youth Prison Model, which rejects the harmful, ineffective, and excessively expensive youth prison model in favor of investment in community-based alternatives that work.

Sources

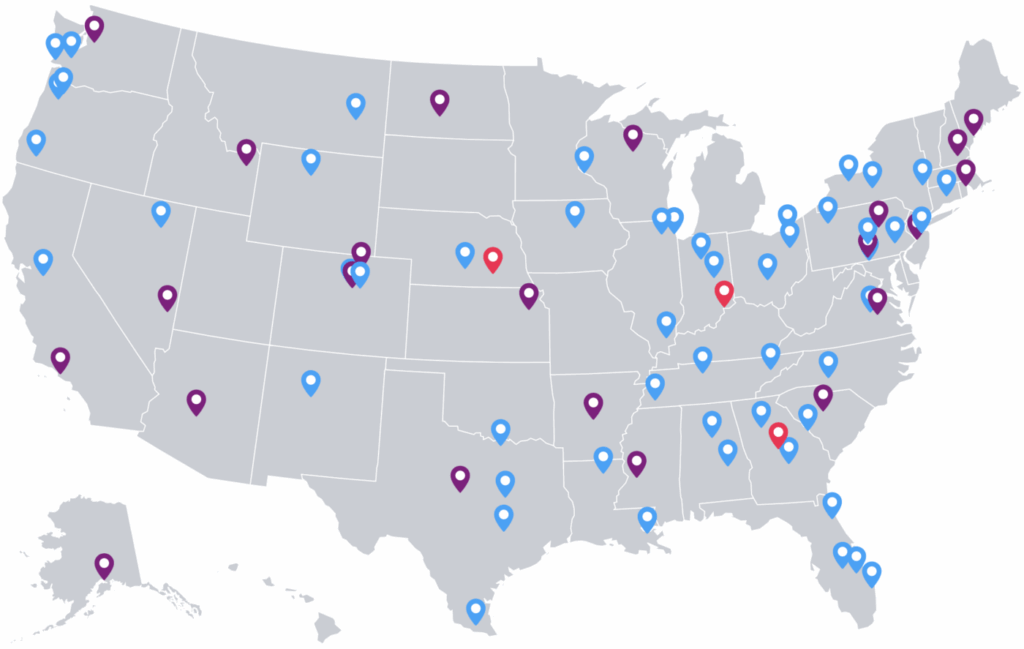

The map above identifies approximately 80 facilities in the U.S. that were established more than 100 years ago or have 100 beds or more. Facility information was collected from state juvenile justice, youth services and correctional departments, websites, and other public sources including state agency annual reports, state fact sheets, departmental budgets and planning documents, and Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA) audits.

The map above identifies approximately 80 facilities in the U.S. that were established more than 100 years ago or have 100 beds or more. These youth prisons are primarily state-run facilities that provide long-term, post-adjudication confinement for youth under the custody of the state’s department of juvenile justice or similarly named agency. In a few states, the state agency contracts with private organizations to operate secure confinement facilities. Boys and girls are held at these facilities and, in some instances, are held in the same institution. A handful of these facilities confine post-adjudicated, committed youth, and also detain youth pre-adjudication or for a period of time post-adjudication while they await an alternate placement.

Youth prisons are a relic of the past; an approach that came into existence in the late 1820s. Youth prisons embody facility features common to adult prisons, including large bed capacity (over 30 beds); correctional staff whose main role is to count and cuff youth; locked rooms, cells or units; razor wire fences; and practices similar to those used in adult prisons, including use of chemical restraints such as pepper spray; mechanical restraints such as leg irons, handcuffs, wrap restraints and hogtying; use of isolation and solitary confinement; and documented instances of physical and sexual violence, physical and verbal abuse, and neglect such as underfeeding and removal of sanitary napkins and toiletry items. Youth prisons are also often geographically isolated, provide minimal contact with family members or opportunity to remain engaged with their communities, and offer limited access to appropriate educational, recreational and other programming.

The inventory does not include all the state, local and private facilities that confine youth under the custody of the juvenile justice system, such as youth prisons under 100 beds, juvenile detention centers (which typically hold youth while the court processes their case but also incarcerate some youth who are awaiting long-term placement), juvenile halls, and assessment centers where youth are sent to receive evaluations to determine whether they will receive long-term commitments. It also does not include youth prisons that incarcerate youth adjudicated in the adult criminal justice system. Over time, the inventory will be expanded to include all of these kinds of facilities.

Through Their Eyes: A Snapshot of the Daily Lives of America’s Incarcerated Youth

For many young people, entering a youth prison closely resembles the experience of entering an adult prison. Uniformed guards bring in young people restrained in handcuffs and leg irons, pat-frisk or strip search them, issue them institutional undergarments and jumpsuits, and then lock them into cell blocks. The emphasis on order and control within youth prisons discourages normal adolescent behavior. In many facilities, youth are expected to walk in single file lines with their hands behind their backs and often cannot speak to each other when they walk or even when they eat. Youth who disobey rules can lose “privileges” such as recreation, showers, or phone calls home. Staff are often trained to manage youth who act out by using solitary confinement, physical restraints or, in some cases, chemical restraints such as pepper spray.

– B.H., age 17

The closed nature of these facilities makes young people vulnerable to sexual and physical abuse. A Bureau of Justice Statistics survey found one in ten youth in youth prisons have been sexually victimized. The survey also found that youth identifying as LGB experienced youth-on-youth sexual assault 10 times more frequently than heterosexual youth. Young people released from youth prisons have described some institutions as “fight clubs” or “gladiator schools” where young people were expected to fight to avoid abuse or where staff actually set up altercations between youth.

Compounding Costs: America’s Youth Prisons are Failing our Kids and Costing Our Communities

Youth prisons harm kids. Incarcerated youth often experience dangerous facility conditions such as physical and chemical restraints, high suicide risk, sexual and physical abuse, and solitary confinement. Abuse in these facilities has increased to more states, according to the latest research by the Annie E. Casey Foundation in ‘Child Maltreatment in U.S. Juvenile Correctional Facilities.’

A wide-ranging and growing body of research exists on how to reduce the likelihood that a youth will reoffend.

Youth prisons cost communities. According to the Justice Policy Institute, in ‘Sticker Shock: Calculating the Full Price Tag of Youth Incarceration’, thirty-three U.S. states and jurisdictions spend $100,000 or more annually to incarcerate a young person, and continue to generate outcomes that result in even greater costs. Compare these costs to the investments in education where the average annual per pupil cost of K-12 public education is substantially lower. Communities aren’t safer as youth experience high recidivism rates and incarceration in the juvenile justice system substantially increases the likelihood that youth will be incarcerated in the adult criminal justice system.

Youth prisons break up families. Youth are often placed in youth prisons far from their families, with limited access and visits. Families are often not included in the treatment plans for youth. And families are paying for at least some of the daily cost of confinement according to the National Center on Juvenile Justice. A new study from the Juvenile Law Center, Debtors’ Prison for Kids? The High Cost of Fines and Fees in the Juvenile Justice System, finds that every state permits juvenile courts to impose system costs on youth and their families, and the impact is felt most by youth of color and youth in poverty. Youth prisons aren’t needed in the first place as the vast majority of incarcerated youth do not pose a risk to public safety. Youth prisons are the most expensive option in the juvenile justice system and consistently produce the worst outcomes. And, recent public opinion polling shows that a majority of Americans think youth prisons should be closed and replaced with rehabilitation and prevention programs that work better to help youth and protect public safety.

The Road Home: Moving from Visualizing the Problem to Actualizing the Solution

In the last decade, formerly incarcerated youth, families of incarcerated youth, lawyers, youth advocates and community members have worked together to organize successful campaigns to shut down notorious youth prisons in severals states, including Louisiana, New York, Mississippi, Texas, DC, and California. Today, several campaigns are seeking to build on these victories by promoting a new model of youth justice in their states.

Anything that can be done in a youth prison can be done in the community, only better.

Led by directly impacted youth, families, & community members, campaigns in states are working to close & repurpose youth prisons, and invest in youth in their communities.

For example:

- In Kansas, the Larned youth correctional facility closed in March, 2017; Comprehensive juvenile justice legislation became law that will reduce reliance on imprisonment; & over $12 million has been invested in community-based programs for kids.

- In Virginia, the Beaumont juvenile correctional center closed in June, 2017; and the Virginia General Assembly approved budget legislation to reallocate the savings from youth prison closures to substantially increase community-based services and programs for youth.

- In Connecticut, on April 12, 2018, the Connecticut Juvenile Training School (CJTS) closed.

- In New Jersey, the Governor and the State Attorney General have announced their commitment to closing two youth prisons and established a statewide task force.

- In Wisconsin, on March 30, 2018, Governor Walker signed legislation to close the Lincoln Hills and Copper Lake youth prisons by January 1, 2021.

I believe it’s long past time to close these inhumane, ineffective, wasteful factories of failure once and for all.

Ted Talk: ‘No Place for Kids‘

These campaigns are carrying out a range of activities to build support for community alternatives to youth incarceration, including organizing community forums and film screenings, lifting the voices of young people and families affected by the system, and sharing research and data about best practices in youth justice. Explore our state partner campaigns here to see whether you can get involved in your state.